Vitamin D-dependent rickets type 1A due to pathogenic variant in CYP27B1:Case report

Authors

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.37980/im.journal.ggcl.en.20252759Keywords:

Vitamin D–Dependent Rickets Type 1A, CYP27B1 Protein, Hypocalcemia, Pathologic Fractures, Infant, Genetic TestingAbstract

Clinical case: This is a case report of a one-year-old male infant with a history of chronic malnutrition and global developmental delay who was admitted to the Dr. José Renán Esquivel Children's Hospital with community-acquired pneumonia complicated by septic shock. Clinical and radiological findings: During his hospitalization, severe mineral metabolism disorders, multiple pathological fractures, and radiological findings consistent with severe rickets were documented. Biochemical findings: Biochemical studies revealed persistent hypocalcemia, marked elevation of alkaline phosphatase, and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Molecular diagnosis: Molecular study by whole exome sequencing identified a homozygous pathogenic variant in the CYP27B1 gene (NM_000785.4:c.602_611del; p.Val201AlafsTer31), confirming the diagnosis of vitamin D-dependent rickets type 1A. Treatment and outcome: Treatment with alfacalcidol and calcium supplementation was initiated, with a favorable initial clinical and biochemical response. Conclusion: This case highlights the importance of timely recognition of genetic forms of rickets and the use of effective therapeutic alternatives in settings where calcitriol is not available.

Introduction

Rickets is a disorder characterized by defective mineralization of the growth plate cartilage, occurring exclusively in children and clinically manifested by bone deformities, growth retardation, hypotonia, and, in severe cases, pathological fractures [1,2]. Although the most frequent cause worldwide continues to be nutritional vitamin D deficiency, there are hereditary forms of rickets that require a specific diagnostic and therapeutic approach [3].

Vitamin D–dependent rickets type 1A (VDDR1A; OMIM 264700) is a rare autosomal recessive disease caused by mutations in the CYP27B1 gene, which encodes the renal enzyme 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1α-hydroxylase [4]. This enzyme is responsible for converting 25-hydroxyvitamin D into 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol), the biologically active form of vitamin D [5]. Deficiency of this enzyme leads to persistent hypocalcemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, hypophosphatemia, and elevated alkaline phosphatase, with progressive skeletal involvement [6].

The standard treatment for VDDR1A consists of administering active vitamin D (calcitriol) together with calcium. However, in many Latin American countries access to calcitriol is limited; therefore, alfacalcidiol represents an effective and safe therapeutic alternative [7,8]. Below, a representative clinical case with severe manifestations and molecular confirmation is presented.

A one-year-old male infant from a rural area, with a history of inadequate feeding and no prior supplementation with vitamin D or other micronutrients. He presented with generalized hypotonia and global developmental delay, without independent ambulation. Chronic malnutrition was also documented. No known family history of rickets or other hereditary bone diseases was reported.

He was admitted due to progressive respiratory distress, fever, and irritability. On initial physical examination, he had hypoxemia, subcostal retractions, and poor peripheral perfusion, rapidly progressing to septic shock of pulmonary origin.

Hospital course

During the acute respiratory phase, community-acquired pneumonia was diagnosed, requiring management in the intensive care unit, high-flow oxygen, and vasoactive support with norepinephrine. During hospitalization, blood cultures were positive for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Klebsiella pneumoniae; consequently, targeted antibiotic therapy was indicated. During comprehensive evaluation, abnormal skeletal findings were identified, prompting directed radiological and metabolic studies.

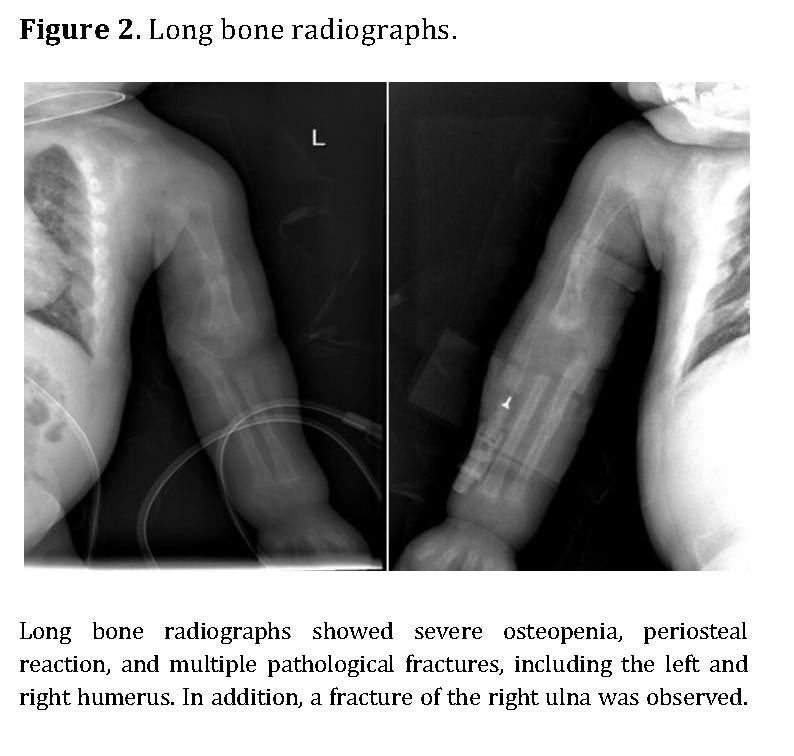

Chest radiography showed bilateral heterogeneous parenchymal infiltrates, pleural thickening, and right-sided rib fractures in the consolidation phase (Figure 1). Radiographs of long bones revealed severe osteopenia, periosteal reaction, and multiple pathological fractures, including the right and left humerus, right ulna, and right femur (Figures 2 and 3).

Laboratory results

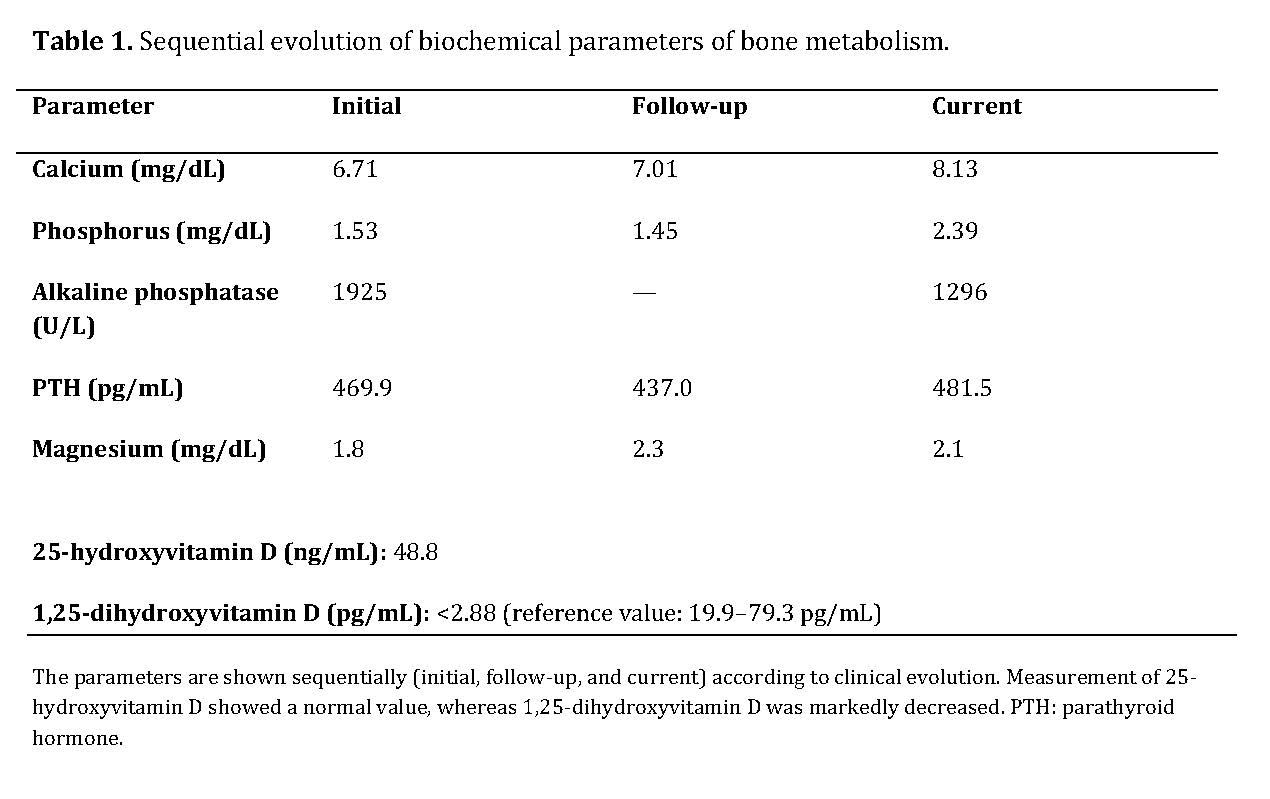

Biochemical studies revealed severe disturbances of mineral metabolism, with persistent hypocalcemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, markedly elevated alkaline phosphatase, normal levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and a marked decrease in 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.

The combination of a calcipenic rickets pattern—characterized by hypocalcemia and hypophosphatemia, severely elevated alkaline phosphatase, and secondary hyperparathyroidism—together with normal 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and a marked decrease in 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D is highly suggestive of a defect in vitamin D activation.

The diagnosis was supported by integration of the clinical, radiological, and biochemical findings, consistent with congenital rickets. In this context, the observed biochemical profile was compatible with 1-alpha-hydroxylase deficiency, corresponding to vitamin D–dependent rickets type I from a pathophysiological and biochemical standpoint.

The sequential evolution of biochemical parameters is summarized in Table 1, showing persistent hypocalcemia, marked secondary hyperparathyroidism, and a progressive decrease in alkaline phosphatase after initiation of treatment.

Molecular study

Molecular analysis was performed by whole-exome sequencing in an accredited external laboratory (BGI Clinical Laboratories), identifying a homozygous pathogenic variant in the CYP27B1 gene (NM_000785.4:c.602_611del; p.Val201AlafsTer31). This variant corresponds to a 10–base pair deletion that generates a frameshift and a premature termination codon. As a consequence, a truncated and nonfunctional protein is produced, with loss of renal 1α-hydroxylase activity, preventing calcitriol synthesis and explaining the observed clinical phenotype.

Treatment and outcome

Replacement therapy with alfacalcidiol and calcium gluconate adjusted to weight and biochemical response was initiated, along with intensive nutritional support and conservative orthopedic management. The patient showed progressive improvement in clinical status and adequate oral tolerance, but with difficulty stabilizing biochemical parameters, requiring prolonged hospitalization.

Discussion

VDDR1A is an uncommon but severe cause of calcipenic rickets, whose diagnosis is often delayed due to clinical similarity with nutritional vitamin D deficiency [4,6]. Deficiency of the renal 1-alpha-hydroxylase enzyme prevents conversion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, explaining its markedly reduced levels despite normal 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Reduced active vitamin D leads to decreased intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorus, resulting in hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, and secondary hyperparathyroidism, as well as increased bone turnover reflected by severe elevation of alkaline phosphatase, characteristic of calcipenic rickets [4].

Frameshift mutations in CYP27B1 are associated with complete loss of enzymatic function and more severe phenotypes, characterized by profound hypocalcemia, marked secondary hyperparathyroidism, and early skeletal involvement [9–10]. The variant is reported in the ClinVar database (Variation ID: 3575036), where it has been classified as likely pathogenic. However, considering that it is a truncating loss-of-function variant in a gene for which this mechanism is a known cause of disease, its detection in the homozygous state and the clear concordance with the patient’s clinical phenotype, the variant was classified as pathogenic according to the criteria of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). The pathogenic classification was primarily supported by criterion PVS1, complemented by criteria PM2 and PM3. In this context, the use of in silico bioinformatic predictors was not considered necessary.

Molecular diagnosis allowed confirmation of the etiology, guidance of the specific treatment that had already been initiated based on biochemical diagnosis, and provision of genetic counseling to the family.

Calcitriol is the treatment of choice; however, multiple studies have shown that alfacalcidiol is an effective alternative when calcitriol is not available, as it only requires hepatic hydroxylation for activation [7,8,11]. In Latin American countries, where calcitriol availability may be limited, alfacalcidiol represents a safe and cost-effective therapeutic option, provided that close monitoring of serum calcium and phosphorus is performed [8,12].

Abbreviations

VDDR1A: Vitamin D–dependent rickets type 1A; PTH: Parathyroid hormone; FA: Alkaline phosphatase; 25-OH vitamin D: 25-hydroxyvitamin D; 1,25-(OH)₂ vitamin D: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol); ICU: Intensive Care Unit; ESBL: Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase; OMIM: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man; CAP: Community-acquired pneumonia.

About the authors

KC: resident physician in clinical genetics; OS: pediatric clinical geneticist; KS: treating pediatrician; HL: pediatric endocrinologist.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jorge D. Méndez for his guidance in the publication of this manuscript as a professor of the Clinical Genetics Residency Program at Hospital del Niño, Panama.

References

[1] Thacher TD, Fischer PR. Vitamin D–deficiency rickets. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(3):248–254.

[2] Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):266–281.

[3] Carpenter TO, Shaw NJ, Portale AA, Ward LM, Abrams SA, Pettifor JM. Rickets. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17101.

[4] Wang JT, Lin CJ, Burridge SM, Fu GK, Labuda M, Portale AA, Miller WL. Genetics of vitamin D 1α-hydroxylase deficiency in 17 families. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63(6):1694–1702. doi:10.1086/302156.

[5] Christakos S, Dhawan P, Verstuyf A, Verlinden L, Carmeliet G. Vitamin D: metabolism, molecular mechanism of action, and pleiotropic effects. Physiol Rev. 2016;96(1):365-408. doi:10.1152/physrev.00014.2015.

[6] Fraser DR. Vitamin D–dependent rickets. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1989;18(3):637–648.

[7] Baroncelli GI, Bereket A, El Kholy M, Audì L, Cesur Y, Ozkan B, et al. Rickets in the Middle East: role of environment and genetic predisposition. J Endocrinol Invest. 2018;41(8):873–885.

[8] Pettifor JM. Calcium and vitamin D metabolism in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25(9):1839–1848.

[9] Demir K, Kattan WE, Zou M, Durmaz E, BinEssa H, Nalbantoğlu Ö, et al. Novel CYP27B1 gene mutations in patients with vitamin D-dependent rickets type 1A. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e012.

[10] Tebben PJ, Milliner DS, Horst RL, Harris PC, Singh RJ, Wu Y, et al. Hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, and nephrocalcinosis in CYP24A1 deficiency. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2017;46(4):875–893.

[11] Uday S, Högler W. Nutritional rickets and osteomalacia in the twenty-first century: revised concepts, public health, and prevention strategies. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2017;15(4):293–302. doi:10.1007/s11914-017-0383-y.

[12] Kitanaka S, Takeyama K, Murayama A, Kato S. Molecular basis of vitamin D-dependent rickets type I. Bone. 2001;27(3):369–374.

suscripcion

issnes

eISSN L 3072-9610 (English)

Information

Use of data and Privacy - Digital Adversiting

Infomedic International 2006-2025.